Slider

慈荫庵和梨花素食餐厅

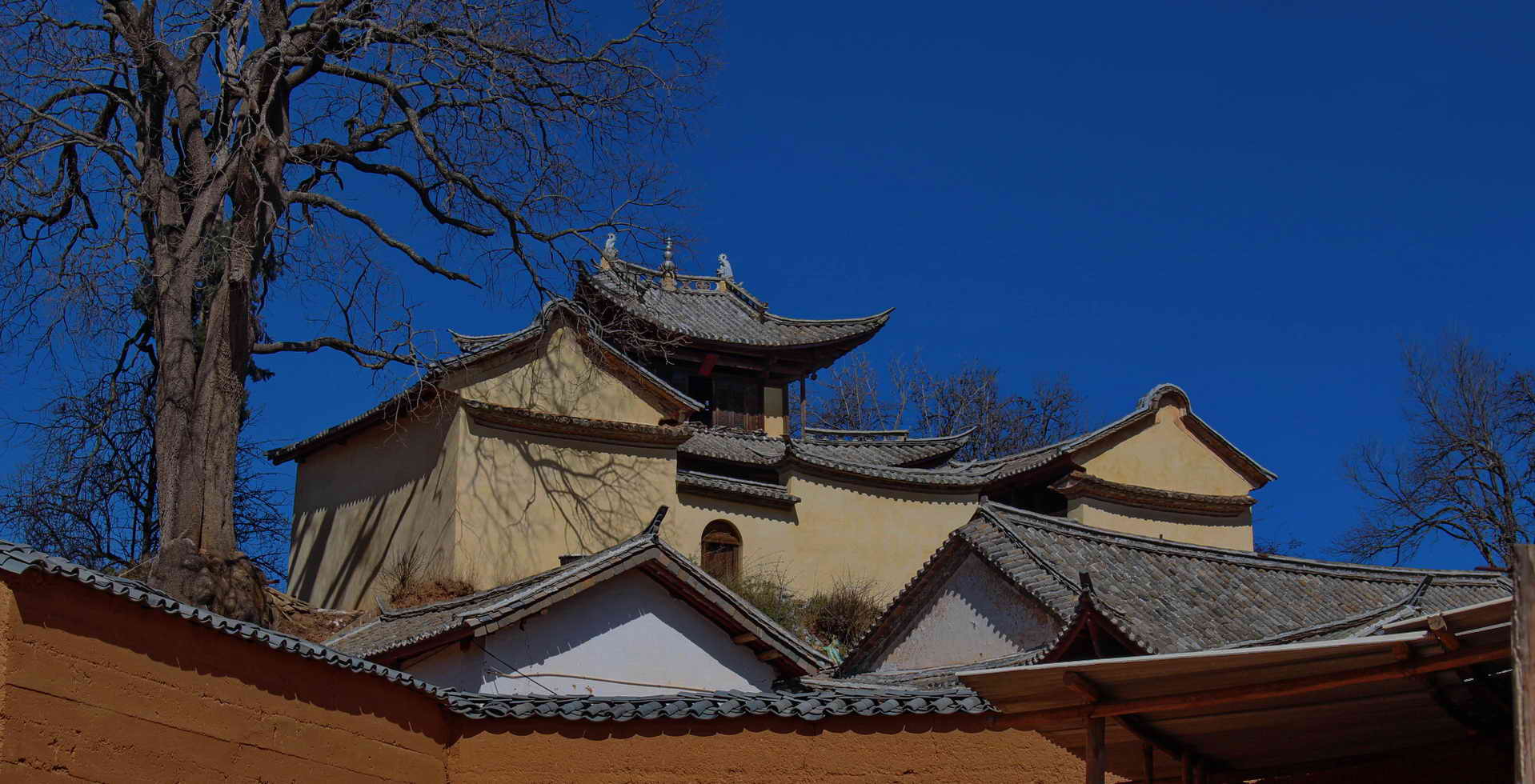

古老的慈荫庵位于甸头村北端,地势绝佳,在这里可以纵览整个沙溪的壮观景色。这里原本是一座尼姑庵,但随着宗教影响力的衰落,这里也日益荒废,然而人们依然前来虔诚的朝拜送子观音。2010年冬季的一天,一个名叫柏昆(Chris Barclay)的美国游客和妻子Nam来到了沙溪,听说慈荫庵的送子观音很灵验,他带着时年45岁的妻子前来朝拜祈求子嗣,回去后如同奇迹般生了一个漂亮女儿。2011年,他带着感恩的心情回来还愿,获得了当地政府的修复许可后,个人出资并遵照地方政府文物修复的要求,由大理国光古建园林公司施工,用本地传统工艺高标准修复了这座古老而神秘的寺院,并为了给访客提供简单寺院餐饮,在南厢房打造了朴素典雅的梨花素食餐厅。您可以在此处了解有关他们 真实故事的更多信息。 通过与当地政府和村民的友好合作,已有300多年历史的古老寺庙进入了全新的旅游发展阶段。现在,现代化的游客中心已经投入使用,在舒适的咖啡厅里吃块小面包,或是细细品尝本地美食,同时可以观看各种关于沙溪历史文化介绍的视频,还可以轻松获得旅游资讯。寺庙的最高层躲在巨大的古树背后,游客可以在顶层的露台上享用丰盛的本地素食,或是悠闲的喝上一顿下午茶。

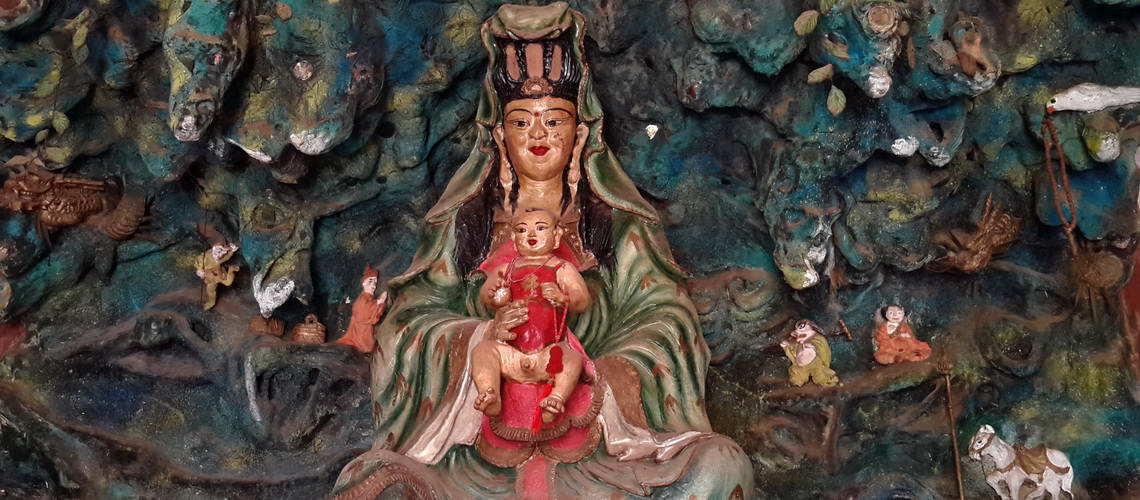

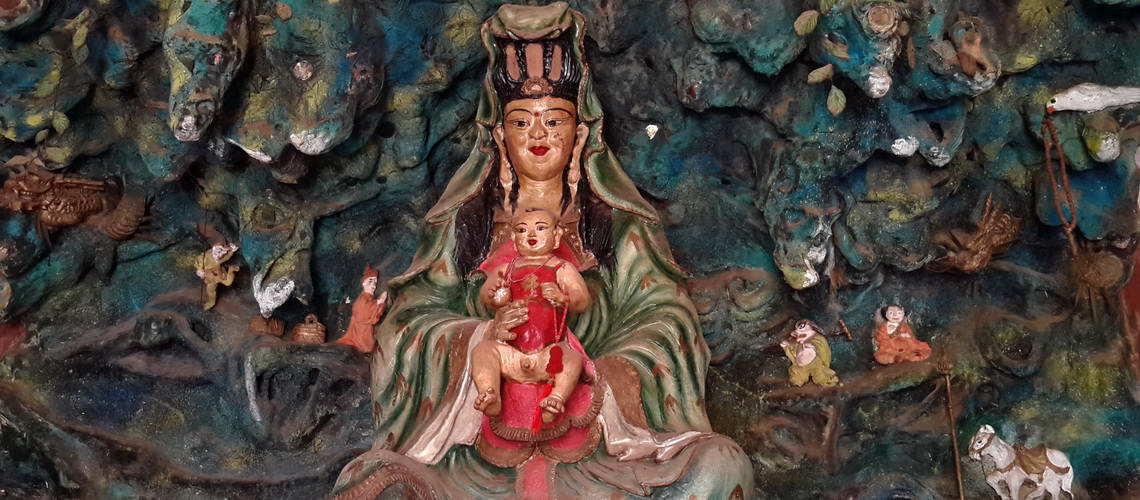

THE GODDESS OF MERCY

Above the main courtyard is the Hall of the Goddess of Mercy or Goddess of Compassion (Guan Yin 观音). In this shrine, the Mother Goddess is depicted with a baby as Songzi Guanyin (The Guan Yin Who Brings Children 送子观音). The name Guanyin

is short for Guanshiyin, which means "Perceiving the Sounds (or lamentations) of the World". It is the Chinese translation of the Sanskrit name Avalokitesvara, the Indian bodhisattva of wisdom and compassion, the unfailing savior

of all beings. Guanyin is revered in the general Chinese population due to her unconditional love, compassion and mercy. In Chinese Buddhism, she is the Mother Goddess, the great protector and benefactor of the weak, the ill and especially children and the babies. By this association she is also seen as a fertility goddess capable of granting children. In Daoism she is revered as Songzi Niang Niang, the Maiden Who Brings Children. An old Chinese belief involves a woman wishing to have a child offering a shoe at a Guanyin Temple. Sometimes a borrowed shoe is used then when the expected child is born the shoe is returned to its owner along with a new pair as a "thank you" gift.

The Barclays, an American family who recently restored the temple, prayed to Guan Yin and after years of not being able to conceive, were blessed with a helathy baby girl, Hannah. You can see their touching video here.

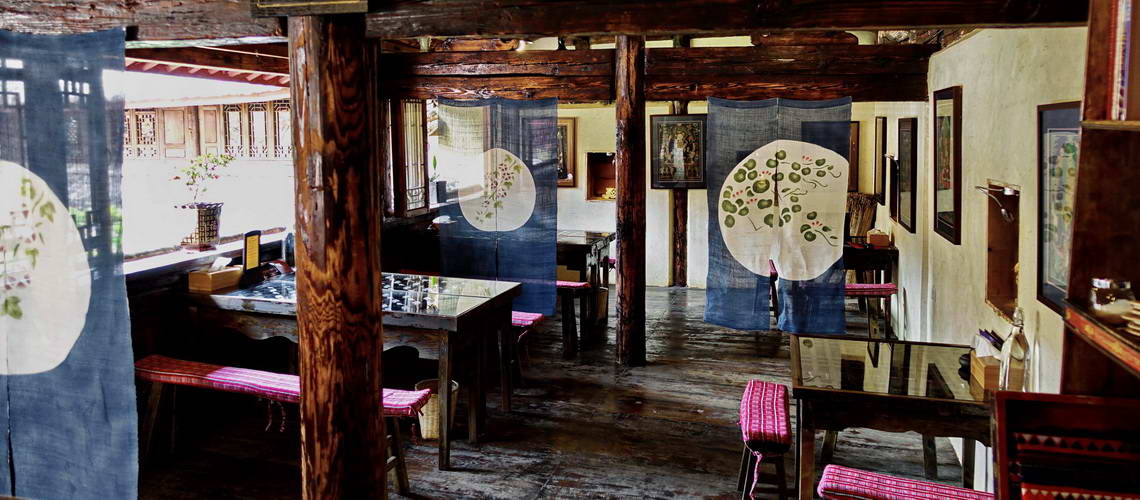

THE TEAHOUSE

Hidden away on the second level of the temple is a quiet hall which overlooks the courtyar. This is the Pear Blossom Teahouse. Designed by project owner Chris Barclay, the teahouse serves lunch and dinner from a seaonal vegetarian menu The Teahouse is not easy to find and most know of it through word-of-mouth. There are no signs in the temple pointing guests inside and so most tourists don't know about it. Our chef, Madam Yang is a resident of the temple's Diantou Village and is a master of local vegetarian cooking. She doesn't speak very much English but she has young assistants who help with foreign guests. There is a broad imported wine selection as well as local beers and of course diverse teas from around Yunnan.

CEREMONIES AND FESTIVALS

Throughout the year, the people of Diantou Village will gather at the Pear Orchard Temple to celebrate religious days. There is a large kitchen reserved for ceremonial and festival cooking, separate from the Pear Blossom. Early in the morning, the village women elders (Lao Mama Hui) will arrive to prepare the kitchen and shrines while the men prepare the many tables and benches required for the large meal to follow. Alms are collected for each occasion to help pay for the cost of food and cermonial items. Those lucky enough to arrive during the time of the month when rituals are performed are welcome to join in and have a meal. A small donation to the temple is recommended.

CULTURAL PERFORMANCE

Chef Yang is also an accomplished traditional dancer and leads Diantou Village's women's dance troupe. Groups can request in advance a demonstration of Bai ceremonial dance and particpate in learning with the troupe. Blessing ceremonies may also be arranged through Madam Yang, who can ask the village priest and women elders to perform a special blessing ceremony for children or those dealing with poor health. At least one day's notice is required to gather the local people who typically have farming and household work to tend to each day.

GUAN YIN

The most popular and beloved of the enlightened beings, Avalokiteśvara embodies the compassion of all Buddhas. Empowered with supernatural powers, she can assume any form, and also has the power to grant children. As the personification of compassion and kindness, the mother-goddess is the patron of mothers. The temple was originally devoted to her, and the original name means 'Sheltered Mercy'.

In the background of her shrine, you can see from left to right Monkey King, Monk Triptaka, Pigsy, Sandy and the magic white horse White Dragon from the Chinese classic 'Journey to the West'. Tripitaka is on a solo mission from the Chinese emperor to India to fetch one of the first sets of Buddhist scriptures back to help spread Buddhism. However because he is an incarnated being, it is believed that anyone who eats his flesh will live forever, so all demons want to eat him alive. Fortunately Guanyin helps him on his mission, and the accompanying disciples complete their pilgrimage and gain redemption for their past sins.

SAKYAMUNI BUDDHA

The main shrine of the upper temple celebrates witness the Buddha’s ascension to the Pure Land. His hand gesture or mudra calls upon the earth to witness Sakyamuni's enlightenment at Bodh Gaya. Here the

Buddha seated on a lotus throne is depicted in Bhumisparsha Mudra where his right hand reaches toward the ground, palm inward. He is accompanied by two sage disciples. Similar depictions can be seen

at the Fahua Temple Grottoes of An Ning near Kunming and at Baoshan Temple at the Shibaoshan Grottoes in Shaxi. Laozi and Confucious.

To the Buddha’s left is an image of Lao Zi 老子 the Founder of

the Daoist School. In his hand he holds dust, symbolizing impermanence and the cycle of life and death. Seated to Laozi’s right, astride a spotted hippo is Confucius (孔子), honoured for bringing cultural

literacy to Chinese people, humanitarianism and a system of social analects that established an ethical paradigm on which Chinese society is still based.

THE JADE EMPEROR

Yù Huáng or Yù Dì in Chinese folk culture is the ruler of Heaven and all realms of existence below including that of Man and Hell, according to a version of Taoist mythology. He is one of the most important

gods of the Chinese traditional religion pantheon. In actual Taoism, the Jade Emperor governs the mortals’ entire realm and below, but ranks below the Three Pure Ones. The worship of the Jade Emperor

is traced to as early as the 9th century AD, when he was the patron deity of the imperial family.

The Jade Emperor is the king of the Universe, and a holy god whose origin goes back to 4th century

China. In Daoism he is the highest holy spirit – and leader of all the gods in heaven. He looks after all matters related to heaven, earth and human beings. Chinese divided the universe into these three

realms: heaven where the holy spirits reside; the earth which is the mother for all forms of life, and human beings. The Jade Emperor governs all three.

The Jade Emperor's Birthday is said to be

the ninth day of the first lunar month. On this day Taoist temples hold a Jade Emperor ritual (Bai Tian Kong), literally "heaven worship") at which priests and laymen prostrate themselves, burn incense

and make food offerings.

The Jade Emperor is a Daoist god who oversees all three realms of existence and sits atop the Sakyamuni building in a separate ornate shrine, only accessible by a narrow

wooden staircase. The elders do not allow young people or women to ascend these stairs. The story of the building of the Jade Emperor hall is featured prominently in the temple’s inscribed historical

tablet.

GOD OF WEALTH

In a separate courtyard, relegated behind and to the right of Guan Yin is Cai Shen (财神) the God of Prosperity that originates from Han Chinese folk legend dating to the Qin Dynasty. Cai Shen is portrayed

astride a tiger holding a golden sword. There is an annual Festival of the Prosperity God every April at the temple, with a large turnout of villagers who raise money, leave offerings at the Cai Shen

altar, hold ceremonies and cook meals all day for attendees.

Cai Shen is the Chinese god of prosperity both of religious Taoism and in folk religion. Though Cai Shen started as a Chinese folk hero,

later deified and venerated by local followers and admirers, Taoism and Pure Land Buddhism also came to venerate him as an immortal. He has various magical powers, such as warding off thunder and lightning,

and ensuring profit from commercial transactions. As a historical figure he is identified as Zhao Xuan Tan, "General Zhao of the Dark Terrace", from the Qin Dynasty. He attained enlightenment on top

of a mountain. He also assisted Zhang Dao Ling on his search for the life-prolonging elixir. Cai-Shen is portrayed riding on a black tiger, on his head he wears a cap made of iron and he holds a weapon,

capable of turning stone and iron into gold. He carries in his other hand a gold ingot, representative of wealth.

The god of Wealth has an important role to play for humans, ensuring all are free

from poverty and can enjoy abundance. He features in both Buddhism and Daoism. Cai Shen's name is often invoked during the Chinese New Year celebrations in temple festivals.

Next to the God of Wealth

is the God Of Grains, a god held in high regard by communities who are reliant on agriculture. The god covers not just grains, such as rice, but all vegetable (non-animal) foods, including fruits, vegetables,

and grains, as well as plants which grow in water and climbing plants which grow in the air. The god of Grains not only protects all these food sources from disease, pests and disaster, but also ensures

that farmers enjoy a bountiful harvest with enough surplus to store for winter.

GREAT BLACK SKY GOD (Mahakala in Sanscrit)

Mahakala is a protector deity featured prominently in Tibetan Buddhism. A manifestation of the Hindu god Shiva, the god of Time and the time beyond death, depictions of Mahakala usually have two identifying

features: the deity is typically presented in the dark color black, symbolizing how all names and forms are absorbed and dissolved into absolute reality and Mahakala usually has many arms. Another identifying

feature is a crown of five skulls, which represent the five negative afflictions which are transformed into the five wisdoms. In Tibetan Buddhism, he is viewed as the main protector of the Buddhist teachings,

as well as a god of medicine and wealth, and as a manifestation of death. Mahakala is one of the most popular local village protector gods in NW Yunnan (known as Benzu).

Sitting next to Mahakala

is Mother Eath (Parvati in Sanscrit). The goddess of all lands and power, she takes care of the balance between Ying and Yang energies. She is also worshiped as the god of harvest. Parvati is the wife

of Shiva, and she is often depicted sitting astride a tiger.

BODHIDHARMA

The first Zen Buddhist master in China, he was a Buddhist monk who grew up in south India in the 5th century, but he traveled by sea to China and later crossed the mighty Yangtze River to introduce Buddhist practice to China. One of his famous sayings was: Zen points directly to the human heart. See into your nature, and become Buddha'.

THE 18 ARHATS (DESCIPLES)

They are the early disciples and original followers of the Buddha, whom that reached state of Nirvana and are free of worldly cravings. They are charged to protect the faith, to wait on earth for the coming of" Maitreya " the future Buddha. They are depicted here displaying various feats of their legendary feats of spiritual magic.

From China Building Restoration blog

Q&A with Chris Barclay

Q: What were your immediate key intentions for restoring the Pear Orchard?

The first was to restore it with integrity; not just some ad-hoc fixes or cosmetic touch-ups, but a complete job that would keep the temple intact for the next 100 years. The second would be to balance the secular and the sacred; to promote tourism, run a vegetarian restaurant and all while encouraging continued attention to religious traditions in the temple. The third was to make it self-sufficient; not necessarily to make a lot of money, but to pay for the staff working there, allow us to donate to village activities and be able to re-invest in the people and place.

Q: What (if any) is your longer-term goal behind this restoration project?

I’d like to see the temple become a regular venue for traditional arts and music as well as an educational center for Shaxi heritage.

Q: Please summarise your view what sustainable tourism means and how best to implement this in a project like the Pear Orchard. From your presentation I understand that you have a very focused approach to sustainable tourism and I’d like to add that in as I think it’s important to have these wider-reaching ideas when approaching restoration projects.

It’s important that sustainable tourism give a lot of participation and ownership to local people and not require major infrastructure projects to expand. Shaxi’s small roads are perfect for bikes and the existing trails suit horses and hikers. None of these things has much of a footprint (horses consume hay from rice harvests) and we don’t need bigger roads or huge hotels to improve the long-term growth of tourism in Shaxi. Therefore, the Visitor’s Centre in the temple will encourage guests to participate in village tours, horse trekking, hiking and biking, whereby there are a lot of opportunities for interaction with local people who can also offer services in their area, without the need for any kind of “Official” tourism district.

Q: Please give a summary / list of the order of how you approached discussions and decision making at the beginning of the project. Did you simply ask around the village and then hold gatherings with the elders? At which stage of discussions did you involve local government? When did you find the local tradesmen?

When my wife and I first came to the temple in February 2011, we had a look around and I immediately felt sad that this place was kind of abandoned and run down, as it would have made a great place for a teahouse. I explored the idea of some kind of food & beverage concept in the temple throughout 2011 and began to realize that it really wouldn’t work without some serious rebuilding. When my daughter was born in mid-Jaunary 2012, my wife said if we really wanted to do something in Shaxi, we should start with rebuilding the temple. I had met with the government informally a couple of times in 2011 to explore possibilities, get introductions to village elders and by January 2012, I was ready to commit to a full rebuild. The approvals came quickly, with the government supporting our idea to the village and helping secure a win-win agreement. There were a few lunches and dinners with the elders and the County Heritage Bureau, by my March 2012, we were ready to begin work. The construction team all came from Duan Village, and were introduced to me by the owner of a guesthouse in that village.

Q: At what stage did you contact UNESCO? To what extent were/are they involved?

At the beginning of the project, I began looking at UNESCO Southeast Asia website, to find out how other people were approaching multi-use heritage property restoration. They have Heritage Awards every year, so I looked at the key requirements, guidelines and questionnaires they use in the application process. I didn’t think our project was worthy of submitting but as it grew in scope and investment, I began to consider submitting and did so in 2014. We didn’t win, but the head of UNESCO’s Bangkok Office personally wrote me and asked me to resubmit for 2015, which I did, and again, didn’t win. I attribute this to competing against much better funded projects that deal with more culturally significant sites. As far as I know, nobody from UNESCO came to see our work, but they may yet, as they are very interested in how the temple will function in the years following restoration. That is, will we have kept our promise to improve tourism development in our village and beyond without having any negative impact on religious practices and other traditions at the temple.

Q: Please summarise your responsibilities or role towards the Pear Orchard. What was the final agreement between you and the other parties involved as to your role in this project?

Our covenant with the Diantou Village Government and Elders Council is that I will take custodianship of the temple for 30 years while refraining from any activities that would damage the space or disrespect the local people who use it. I hired some local women from the village and have them look after day-to-day functions as well as cooking for guests.

Q: Before starting, did you have to catalogue anything / everything? If so, who made that demand and where did that info go?

My Master Carpenter, Mr. Yang and I took lots of pictures of everything before, during and after construction, especially artwork on plaster that had to be removed and repainted. It was in our interests to do so in order to show the government the extent and quality of our work, as well as for me to monitor progress when not in Shaxi and share with those interested on our website.

Q: Please describe in one or two sentences what the Pear Orchard site was like before you started renovations.

It was a functioning temple with most non-worship spaces used for furniture and kitchen storage related to temple festivals. The roofs leaked, a lot of woodwork was rotten or missing, the trees were dying. There were a lot of ugly ad-hoc fixes like cementing and painting over broken things. Older people from the village would come and play Mahjong there and even dry their vegetables in the courtyards. One thing I noticed was that the temple wasn’t open every day and the main gate was often locked. If people wanted to play cards or worship, they would have to get the man with the key. This is how most temples in Shaxi are today.

Q: Please give a list of all the major works that had to be done. Plumbing, heating, wiring, shoring, foundations, structural work, carpentry, etc.

We completed major work on all the areas you’ve mentioned here, plus lighting, fire detection and suppression, interior decoration for the restaurant, new stairs to the upper shrine, two new retaining walls, a reinforced concrete terrace with railings, parking and new public toilets. We found a corner stone inscribed with poetry, an ancient carved stone footing that we excavated when rebuilding a wall and iron spikes that were used as nails. We also found the buried foot of one of the old lion dog temple guardians that were likely smashed during the Cultural Revolution.

Q: Please give 3-4 examples of areas where you did restoration / repurposing work. Can you give specific examples of a building method, or a traditional material, or style that was implemented as part of the restoration works. For example repurposing timber for rafters, floors and beams. Or perhaps the restoration work came in more to play for decorative items like windows and roof tiles.

The women on site hand cleaned every single roof tile we had removed before putting them back. We bought mud brick from a farmer’s collapsed bar to supplement the mud brick we had to tear down, as this building material is not locally produced any more. We used broken window lattice to make tables for the restaurant and rafters to make the reception desk and service station. All the wall rendering was done on site, using a mix of lime, clay and pigment. The wood floor joint compound was home made on site from ash and tree resin. We did not paint any of the new wood, but used teng oil and ink to match the color of the existing wood.

Q: Were there any unexpected problems or issues that arose during the construction process? Was there any area where you had to improvise / compromise etc. on something unexpected? Was there anything that was out of your control?

One issue was how much dirt and cement had to be excavated to find original foundations and then adjusting pillar footings and floor walkways, which required removing and refitting every piece of stone. We often had to reset floors 20cm below existing levels, which meant removing tons of earth. The biggest issue we had was we had piled all of the rotten wood at the side of the temple, which was to be a garden and parking area. The elderly ladies of the village wanted to keep this wood for kitchen fuel, so without warning, they built a reinforced concrete block storage right up against the temple wall in the middle of this area. We couldn’t just knock it down and no one in the village would take responsibility for it. We suggested moving it to another part of the village, but no one wanted to get involved in this. It took many months of going around and around the problem, with every local government official pushing responsibility for resolving this to another department. So we finally agreed to compensate the ladies for their illegal building as well as pay to build a new one, where they could also keep much of the benches and tables for village festivals. This is China.

Q: Could you give one or two examples of where you had to make a judgment call and the reasoning behind your decisions? For example, the restaurant, because it emphasises how functions have to adapt with the times in order to keep these spaces relevant.

It was not a problem for the government to allow us a restaurant in the temple, but we did not have a kitchen. There are two existing kitchens, both for village festivals and not suitable for modern, small scale cooking. When we wanted to build a kitchen for the restaurant, we looked at a reading room that was also being used for storage. This reading room did not house any shrines or articles of any importance to the village or temple, but was at some point important for ceremonies, as the room used for banner calligraphy and keeping religious texts. Since this room was no longer in use and the elders had been using other space more conveniently located in the lower courtyard for making banners, we chose to create the new kitchen here. Had we tried to recreate the room for its original intended purpose, it would have rarely if ever been used.

We also chose lighting in the main hall where none existed before. For the main lights we chose traditional Chinese temple lanterns and additionally I designed a pair of nesting lights that resemble temple incense coils. We asked the elders about both of these and as with most of our suggestions they were enthusiastic, since it was such an improvement over what was there before (in this case, there was not even electricity in the building). The incense coil lights are unique and match the actual incense coils hanging in the hall, so I took license to put them in there, believing that if anyone objected to them, I could easily replace them with another set of traditional lanterns.

Q: What do you see happening to the Pear Orchard over the next 5 years?

It’s hard to say anything with certainty about foreign managed heritage buildings in China. Government policies often suddenly change without notice. Some fires in important buildings in China has made the government unwilling to allow situations like ours at the Pear Orchard Temple, but for now, we have been grandfathered in. We want to expand service for tour and student groups, offer shared workspace to tour guides and artists, hold photography exhibits and music festivals. We will need someone like a curator to make some of these things happen. We intend to offer horse trekking up to the Sihbaoshan Buddhist grottoes and promote family owned businesses in the villages.

Q: What changes to you see in store for the general Shaxi area in the next 5 years?

It looks to be going the way of Dali and Lijiang old towns, but because of its small size, I don’t think Shaxi will ever become this mass tourism center like these places. For sure, there will be a lot more growth here in Chinese tourism and a challenge for the government to create meaningful zoning to prevent music bars, prostitution, discos and nightclub growth in the old town, as has happened everywhere else there are a lot of Chinese tourists. I believe will stay quieter and better managed, as the government has learned from the mistakes of Dali and Lijiang.

Q: Do you have any insights into the route tourism in China will take over the next 5 years?

I do see more and more Chinese who can appreciate quiet and heritage preservation. This is a huge change from even a few years ago, and one that I think will continue. I also see local governments more willing to invest in authentic preservation to encourage tourism In the past, they would just knock down an old building and build a copy of it. More and more, Chinese are supplanting wealthier foreign visitors, but also bring with them bad habits, such as wanting to drive their cars everywhere, zero concept of waste management, being super loud and in general, having no situational awareness. Hopefully our model of development will attract people who can appreciate it and promote to other like-minded people.

Local farm to table specialties

The Pear Blossom organic Shaxi restaurant offers authentic Shaxi local cooking in an active Buddhist temple. The temple's everyday dishes such as tomato and eggs boast a natural, organic flavor that

urban eateries just cannot compare. Rubing, (known locally as youdbap in the Bai dialect) is a delicate goat's cheese, very similar in taste and texture to queso blanco in South America or paneer

in India. While it is usually served fried with a honey or sugar dip. Our specialties include:

• Fresh, handmade Shaxi "Buddha's Hand" pizza

• 10 kinds of jiaozi (dumplings)

• Sweet

and savory baba (a Shaxi spcialty pastry)

• Farm to table organic vegetables

• Fresh goat cheese dishes

• A great selection of Chinese and imported wines from around the world

Advance reservations are required! Call Sam: 13577258117

Learn Shaxi cooking with our temple chef Madam Yang

Duration: 4 hours

Start off on a bike ride with Chef Yang through Shaxi Valley to learn about the foods that have been grown here for millenia. Stop to pick your own vegetables from the fields, grown by local farmers

for their own families and who use no pesticides. If you choose to do the cooking class on a Friday, Chef Yang will take you on a tour of the Friday Market where you will buy ingredients for your

dishes.

Head to the Pear Orchard Temple, a recently restored 500 year-old folk temple where we have build a new kitchen just for cooking classes. Here you'll spend the next 2-1/2 hours preparing

and enjoying four dishes you will cook yourself. Gaze out over the Shaxi Valley from our dining terrace (weather permitting) and enjoy a complimentary pot of tea.

For reservations, speak to Sam

at Old Theatre Inn +86 872 4722 296 or email us in advance of your stay to reserve places in the class.

Ancient religious traditions meet at the Pear Orchard Temple

Dali has a unique form of Tantric Buddhist practice called Acarya, which dates back to the 9th century, traces its origins to India, and features prominently the goddess of mercy Acuoye, represented at Shibaoshan's grottoes carved 1,100 years ago.

Where did it come from?

Buddhism originated in northern India in the 5th century B.C.E., tracing its roots back to Siddhartha Gautama, typically referred to as the Buddha. Over its 2,500 year history Buddhism has evolved and

spread throughout Asia, with three main branches of the tradition: Theravada (in south-east Asia), Mahayana (in north-east Asia) and Vajrayana (in Tibet). Buddhism came to Dali along the Tea Horse

Road, also known as the Southern Silk route, which linked India, Tibet and south-east Asia. Dali played a key role in the spread of Buddhism from India to China, and its Nanzhao (738-902) and Dali

(937–1253) kingdoms were notable for preserving Buddhism and also constructing large temples including the Dali Three Pagodas and Shibaoshan grottoes near Shaxi, which became important centers for

Buddhist teaching.

According to ancient documents, a mystic Indian monk called Zhang Tor Jie Duo is credited with bringing Buddhism to Yunnan's Nanzhao kingdom in 840. From the 9th century onward

to the end of the Dali kingdom in 1253, a brand new powerful branch of Tantric Buddhism formed and developed into a kingdom-wide religion. Later, Zhang Tor Jie Duo became regarded as a manifestation

of the 'lord of compassion' Acuoye. Avalokitesvara (dubbed the Dali Guan Yin or goddess of mercy), who is the main religious figure worshiped throughout Nanzhao and Dali kingdoms. The Acarya branch

of Tantric or Esoteric Buddhism originated from India, and it was mixed with where in its early stages was fused with Brahmanism, the early priestly religion in India which evolved into Hinduism.

Acarya belongs to the Mahayana tradition of Buddhism. Mahayana Buddhism was a more liberal, accessible interpretation of Buddhism, open to people from all walks of life, not just monks or ascetics.

Acarya is a Sanskrit word, meaning teacher or victorious, and in Dali it became known by the Bai minority term 'A-Zha-Li'. A-Zha-Li initially referred to the master who conducted rituals and ceremonies

of this branch of Buddhism, but later the name was used to locals to refer to this practice.

What is unique about Acarya Tantric Buddhism?

1. Devotion to Acuoye

Many Buddhist cults developed during the almost five centuries of the Nanzhao and Dali kingdoms, but Acuoye Avalokitesvara in various forms was the dominant figure and the focus

of devotion. One of the reasons for this was the key role of Acouye in both political and spiritual affairs. There was a strong linkage between the rulers of the Nanzhao kingdom and Acuoye in establishing

both state and religion, with Acuoye featuring in the founding stories of the kingdom, helping legitimize the royal line. According to folk stories, Acuoye arrived in the Dali area even before the

establishment of the Nanzhao Kingdom, appointing its first ruler and providing protection for the kingdom. There was a belief that the royal lineage was approved by Acuoye, and that the rulers and

their descendants were related to Acuoye. The ruling class built the iconic Three Pagoda temple in honor of Acuoye. Acuoye is regarded as the first god to manifest to bring Buddhism to the Bai people,

but there is debate about where Acuoye actually came from. While many scholars think Acuoye is just another manifestation of the Mahayana bodhisattva from India, there is conjecture that this figure

of compassion came from south-east Asia instead. Some researchers speculate that Acuoye came from Malaysia or Indonesia, when in the 9th century one of Nanzhao kings received a bride from 'the realm

of Kunlun'.

2. Black Sky god

While Acuoye holds a central position in A-Zha-Li, other cults of Esoteric Buddhism developed under the Nanzhao and Dali kingdoms, including protective and

wrathful divinities. Second only to Acuoye in popularity and devotion is Mahakala, the Black Sky god in Chinese, a divine demon and protective deity for Acarya Tantric Buddhism. Makakala is in fact

the manifestation of the Hindu god Shiva. Throughout the Dali region many villages regard him as their local protector, or 'ben zhu'.

3. Unique role in society and inheritability of status

While many Buddhist traditions required a separate life for religious disciples from lay people, A-Zha-Li practitioners were able to get married and maintain a normal family life. One of the reasons

for this might be traced back to the establishment of Acarya in Dali, with Nanzhao king Qu Feng permitting his sister to marry Indian missionary Zhang Tor Jie Duo who brought Tantric Buddhism to

the region in 840 AD. A-Zha-Li masters and their descendants were able to continue this lifestyle with its integration into normal life. In Feng Yi village near the Erhai lake this bloodline tradition

lasted for 42 generations among the Dong family, only ceasing with the founding of Communist China in 1949.

4. Variety of Practice

There were three main ways of practicing A-Zha-Li: masters

teaching students from scriptures in secret, and using mantras and magic spells; adoption of body postures and hand positions to practice; and meditation. In addition to the various Buddhist texts,

we know that the Buddhists of Nanzhao and Dali cherished spells and mantras of any kind, and for any purpose. Many were engraved on stone slates and impressed onto clay and bricks. Later, mantras

and spells were engraved on wood and printed on paper. This practice probably dates back to the 9th century in Nanzhao. Interestingly, these mantras and spells were written in Sanskrit. In the rest

of China, mastery of Sanskrit was the domain of only a few select educated people, while around Dali it appears that the links with India and understanding of Sanskrit were maintained.

5.

Death rituals

The A-Zha-Li practices also included death and burial rituals, to guide the deceased along the right path to Nirvana. Even today this aspect of tradition is well preserved and plays

a very fundamental part in the funeral rites of Bai people.

6. Hybrid of religion appears

Buddhism under the Nanzhao and Dali kingdoms wasn't exclusively Esoteric in nature. Before Buddhism

established and spread in the 9th century, the local people practiced a more nature and spirit-based shamanism similar to Bon Buddhism found in Tibet. Daoism, a Chinese-rooted philosophy, was founded

in the 6th century.some of the Dao core concepts get mixed with in later practices too. After the end of the Dali kingdom by Khubai Khan's army in 1253 the Chinese influence increased in the Yunnan

region. In the Ming and Ching dynasty Confucianism became the dominant system for social order, weakening A-Zha-Li. Another important factor is the Southern Silk route, also known as the Tea Horse

caravan route, which brought traders and merchants from different nations holding a wide range of beliefs and practices. This led to the enrichment and development of A-Zha-Li, as it took on-board

these influences, reflecting the diversity of peoples and thought.

What was the impact of A-Zha-Li on Bai society?

The A-Zha-Li Esoteric Buddhist practice was quite widespread during the second half of the 9th century and flourished until the end of the Dali kingdom in 1253. A Chinese scholar Xu Xiake visiting the

region before the fall of Dali described Buddhist practice as 'common in every household, no matter whether they are poor or rich, there is Buddhist ritual space in every family s living rooms. No

matter whether they are young or old, everyone carries a talisman with them. There are many regular days throughout the year when people fast or refrain from eating meat or drinking alcohol. The

number of visible temples and monasteries on hillsides is uncountable.'

A-Zha-Li and politics

A-Zha-Li participated directly in the political life of the region. Governance and religion

became one. Zhang Tor Jie Duo was appointed as strategist of the kingdom after his marriage to the king's sister. Notably of the 22 kings of the Dali kingdom, nine gave up their royal life and retreated

to monasteries to live a monastic life as ordianed monks. A-Zha-Li practices were a vital part of local identity and a source of guidance in turbulence, warring times, with Tantric rituals carried

out to provide supernatural aid in battle.

A-Zha-Li and economics

Large donations and land were made to build and maintain monasteries and temples by the royal family. The monasteries

and temples also held large portions of land and collected wealth. In Dali, the Three Pagodas temple alone had 890 buildings, with 11,400 Buddhist statues made up of 20,295 kilograms of copper.

A-Zha-Li and culture and education

Monks and monasteries became the first schooling system, tutoring students to learn Buddhist texts and classic Confucian teachings. All the artforms including

paintings, architecture and carving show strong influence of A-Zha-Li.

Why did A-Zhal-Li Decline?

Following the conquering of Dali kingdom in 1253 by Kublai Khan, for the first time Yunnan becomes included on maps as part of Greater China. This marked the end of the independent kingdom. After this historic event, A-Zha-Li faced many challenges and gradually declined in strength and prominence. Several reasons for this were because the new ruling class – Chinese – forbid the open practice of A-Zha-Li and sought to reduce its practice and power. The Qing government also suppressed the A-Zha-Li practice, describing it as 'not true Buddhist, not true Daoism, and not true Confucianism, so it confuses and misleads ordinary people to wrong ideas', causing social instability and anarchy. The form of Tantric Buddhism was also frowned upon, particularly as monks were allowed to have families, eat meat and drink wine. The Zhengde emperor banned A-Zha-Li in 1507. Zen Buddhism became popular and also led to the decline of A-Zha-Li, as well as the dissemination of Confucianism by the Ming dynasty. These pressures pushed A-Zha-Li from the ruling and upper classes to common people, where it became a folk religion. Fortunately the ordinary Bai people's preservation of A-Zha-Li and its blending with other religious practices and beliefs kept it alive through the centuries.

The local people who manage the temple on a daily basis are committed to its continuity as a place of workship as well as a window for visitors to better understand Shaxi cultural traditions. The village functions as an informal Visitor's Centre, with maps on Shaxi Low Carbon Tourism, as well as bike rental and horse trekking (Coming 2018). The temple's mission is to first serve the spiritual and community needs of Diantou Village while promoting responsible tourism through those activities where villager's share most of the benefits. These include cooking school, village tours, ceremonial and traditional dance performance, mushroom picking and other local tours organized by hosts from Diantou Village.

The perfect setting for your remote campus

The Pear Orchard Temple is a recently restored Ming Dynasty temple in the heart of Shaxi Yunnan China. In addition to operating as a place of worship and community center for the elders of Diantou Village,

it also features separate classrooms for study and activities. The temple is 10 minutes by bike to family homestay housing in Xia Ke Village, and other housing options are available with local families.

Historic Shaxi Old Town, one of the last intact market towns on the Tea Horse Road in the green foothills of the Himalayas, is just 15 minutes by bike. The temple microcampus features:

•

Three classrooms for 12-15 students in a quiet courtyard overlooking the valley

• Meditation and reading rooms

• Broadband WiFi

• Use of the kitchen or prepared meals

• Activity room

for up to 20 students

• Vegetarian kitchen and restaurant with indoor and outdoor dining

• New modern public restrooms

• Radiant heating in Winter

STAY TUNED FOR 2018 HOLIDAY AND ACTIVITY SCHEDULE

MORE SOON

Prince's Day, Torch Festival Big Buddha Day, Singing Festival

The rebuilding of the Jade Emperor Hall and history of The Temple of Sheltered Mercy

How Buddhism arrived in China 2000 years ago

Buddhism first arrived in China during the reign of Emperor Han Ming (28-75 CE). But it was not until a few hundred years later, when

the Indian missionary Bodhiharma traveled to China that the religion spread across the country. Wherever Bodhiharma went, he gathered great numbers of followers, won over by the ideas of karma, the

will of the universe, fate and destiny; the belief that good will be rewarded in heaven and that evil will suffer in hell after death, and that one can seek one’s true nature by clearing the mind

of everyday distractions.

At first there were no religious books or scriptures available to Chinese Buddhists. People had to learn the teachings by heart and transmit them by word of mouth. The

faithful built many temples, but the practice of making statues of deities only appeared in the Jin dynasty (265-420 CE). From then on, it developed into the standard temple art form we now see everywhere

in China.

In the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE) the valley of Shaxi was flooded and became part of the river bed of the great Yangtze, the third longest river in the world, which flows for 6300 kilometers

through 11 Chinese provinces. At some point the river was blocked upstream by unknown geological events, and its course was diverted to the South from the steep valleys of the West. Half of Shaxi

was covered in water, and the valley was left uninhabited for ages. The southern part of the valley was eroded into a flat, low plain. As time passed, the waters receded and land appeared. Eventually,

during the Ming dynasty, a small group of people originally from Henan settled in the area. These first inhabitants named their settlement Diantou, which simply means “The spot at the head of the

valley”.

Thanks to the influence of Bodhidharma and his teachings, it became the custom that wherever there was a village, there must be a temple. Wherever there was a temple there was a need

to create statues of the various deities, who varied from village to village. Our own temple in Shaxi was relocated three times before being rebuilt on its current location.

Looking at the outline

of the Bell Mountains that surround the valley one cannot help imagining them as a peaceful green dragon, whose spirit guards the villages to the West as he gazes North. The dragon keeps the water

flowing and the forest green, preserving the beauty of Shaxi’s mini-paradise.

The current temple was built in the late Qing dynasty (1616-1912 CE) and is dedicated to the Bodhisattva Guanyin,

the Goddess of Compassion, whose statue is in the central position of the main hall. To the right is the Big Black Sky God, a local deity of the Bai people, and to the left is Bodhidarma. The temple

attracted many pilgrims and the local community raised funds for a community of nuns to maintain the temple and conduct religious ceremonies.

The nunnery is close to Taibai mountain with the

Tianyian hills to the North, facing the jade pagoda to the south with the river visible in the distance. At night, villagers would fall asleep to the sound of the ancient bell’s muffled tolling.

On religious festival days the whole village would be full of music as the villagers celebrated. It was like stepping into an enchanted realm. Travelers who stopped by to enjoy the beauty of this

old nunnery, were assured of a welcome from the head nun, a kind soul who always left the door wide open.

Once, an elderly man arrived carrying statues of the Jade Emperor. He told the head nun

he needed a bed for the night but had to leave early the next morning to deal with an urgent matter and asked could he leave the statues in her safekeeping. But after he left he was never seen again

so the nun thought to herself that it was the Jade Emperor himself who had visited the nunnery. Believing it must be the will of heaven, she decided to build a permanent shrine to the Jade Emperor.

She called a meeting of all the villagers to discuss the project, and everyone agreed to support it wholeheartedly. The rich donated money, the poor people donated their labor, and they completed

the temple in less than six months. The shrine was consecrated to the Jade Emperor in 1917 and on that day everyone from the area came to pay their respects and celebrate. They planted holy pines

all around it so that it became a kind of heavenly place. I was well educated from a young age, and now I am an old man, I still come here from time to time to enjoy the peaceful atmosphere. But

before anyone knew it, the Cultural Revolution broke out. People were scared and confused and took leave of their senses. The nuns disappeared. Some returned to their families or married. The nunnery

was left in a derelict state. People smashed the windows, tore down walls, and threw the gods into the street. Finally someone set it on fire and everything disappeared.

On the night of the fire,

some outlaws planned to steal the statue of the Jade Emperor because it was made of gold, thinking no one would dare to stop them. I was outraged and together with my older brother went to the temple

after midnight and took the statue back to our house where it remained hidden for more than 40 years. We did not even tell our parents about it. Years later when I heard at a government meeting that

the policy towards religion was changing and people would be free to worship again, we decided to rebuild the temple.

Once the news spread, a group of village elders met to discuss how to go

about reconstructing the village temple. Everyone agreed it was a good idea so we approached the rest of the villagers. Every family gave us strong support, so we started to collect donations of

food, money and labour, and chose auspicious dates to start work. We restored the Guanyin hall first, then repaired the Jade Emperor’s palace. Finally, of course, we would have to replace the missing

statue of the Jade Emperor. We decided to wait until after the rice harvest and stage a grand opening to coincide with the harvest festival.

I told everyone not to worry about the statue of the

Jade Emperor, saying I would make a statue myself and bring it to the grand opening. As the time drew nearer my friends kept asking me when I was going to finish the work on the Jade Emperor. I told

them not to worry and when the day arrived I went to temple very early in the morning before anyone was up and about, and carried the Emperor back to his temple. The opening day went really well.

My long years of waiting were over and my wishes had come true. I was a happy man again.

But less than six months later I was thrown into shock and despair when someone stole the golden statue.

We never found out who did it. So we had to replace the original with a copy made of clay.I just had to accept how things had turned out, but it was a terrible loss.

Because our temple is located

in the main village in Shaxi it attracts almost every traveler who visits Shibao Mountain. Not just Chinese but also overseas tourists stop to rest at the temple. So we put a great deal of effort

into maintaining its structure and appearance. We will always value and protect this sacred place and maintain our faith in the gods. The local people here are devoted and generous and are always

willing to work hard to help each other and all the people who pass by.

--As inscribed on marble tablets by a Diantou Village elder - 1982